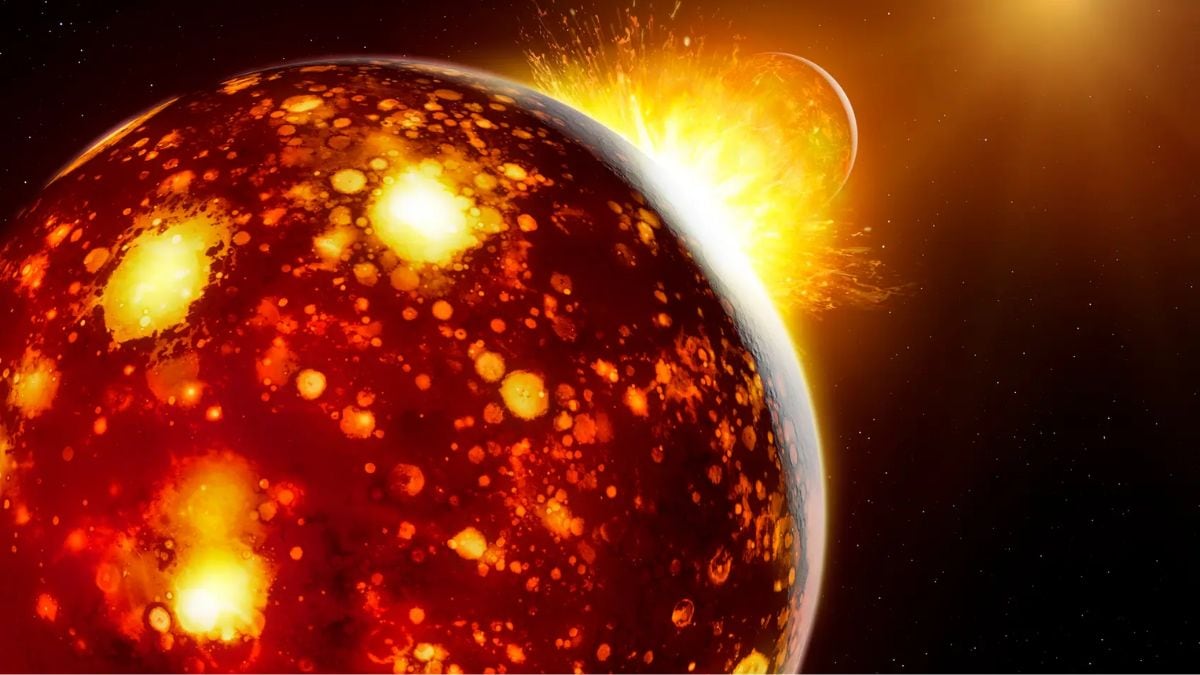

The Moon's formation is attributed to a colossal impact event involving Earth and a Mars-sized body known as Theia around 4.5 billion years ago. A recent study led by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research unveils the origins of Theia by analyzing isotopic 'fingerprints' found in Earth, Moon, and meteorite samples. These findings suggest that Theia and Earth occupied the same region in the inner Solar System prior to the catastrophic collision that created the Moon.

In this study, the team investigated the ratios of heavy-element isotopes, such as iron, chromium, and zirconium, within Apollo lunar rocks and various Earth materials. The results revealed that the isotopic compositions of Earth and the Moon are virtually indistinguishable, and they closely align with data from non-carbonaceous meteorites originating in the inner Solar System. This isotopic signature serves as a key indicator of a celestial body's formation location in the context of the solar system.

By conducting 'mass-balance' simulations that modeled Earth-Theia scenarios, the researchers concluded that the most plausible explanations require both celestial bodies to have formed from materials found in the inner part of the solar nebula. Lead researcher Timo Hopp emphasized that the evidence strongly suggests that Theia and Earth likely constituted neighboring entities during their formative phases.

Furthermore, by contrasting Theia’s inferred isotopic profile with meteorite data, the team discerned that Theia most likely formed closer to the Sun than the current orbit of Earth. This reinforces the theory that Theia shared a birthplace with Earth in the inner regions of the early Solar System, ultimately providing critical insights into the lunar formation processes and the dynamics of our solar system’s early environment.